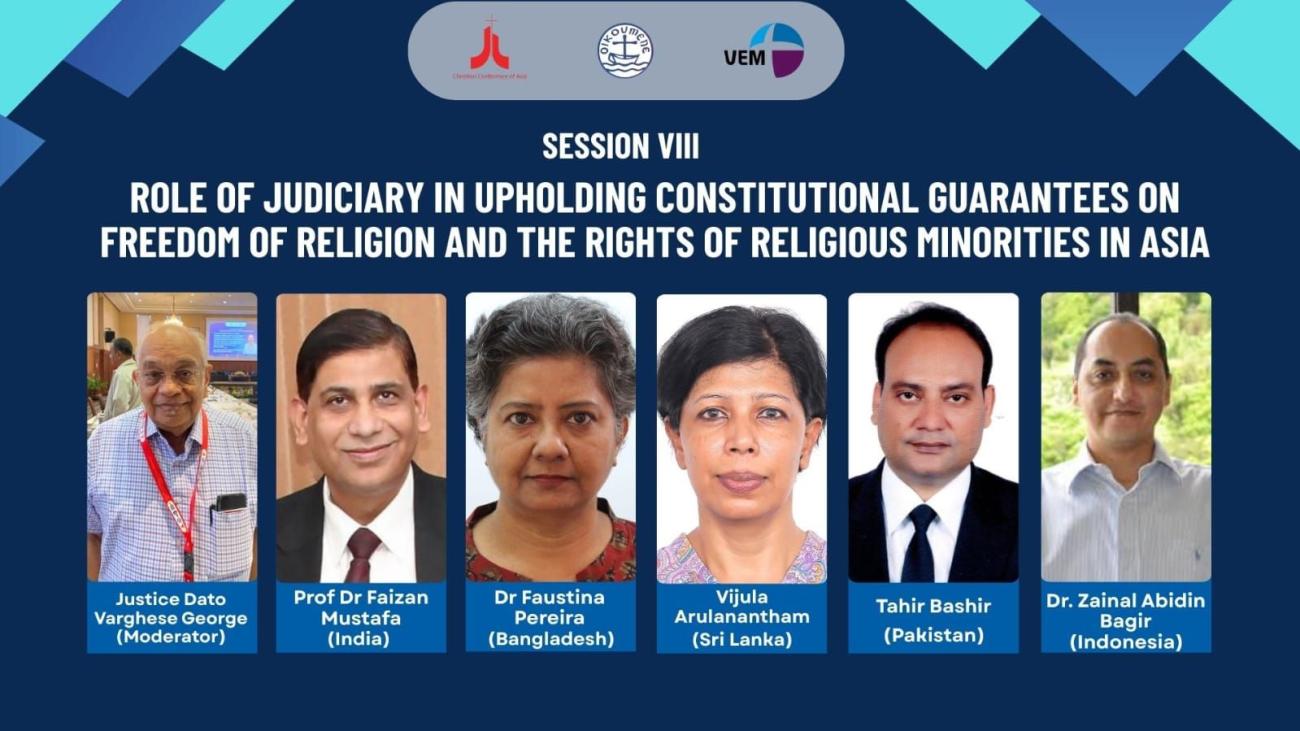

Legal experts highlight judicial challenges in protecting freedom of religion across Asia at Inter-religious Conference in Jakarta

Jakarta, Indonesia: In a panel presentation at the International Inter-religious Conference on Freedom of Religion and Rights of Religious Minorities in Asia, eminent jurists and legal practitioners from across the region underscored the judiciary’s often compromised role in upholding constitutional guarantees of freedom of religion and minority rights.

Justice Dato Varghese George, retired Judge of the Court of Appeal of Malaysia and a former Judge of the High Court in Malaya, reminded participants that courts are expected to serve as “bulwarks against abuse,” protecting rights and laying down clarity through their judgments.

“The courts have a very important role in any nation with a constitution or charter, where human rights are to be respected and protected,” said Justice Varghese George.

Prof. Dr Faizan Mustafa, Vice-Chancellor of Chanakya National Law University, Patna, India, and an internationally renowned scholar in international jurisprudence, emphasised that the judiciary must uphold constitutional guarantees of freedom of religion rather than restrict them.

He noted that while India’s Constitution was framed against the backdrop of partition with a commitment to religious neutrality, some recent judicial decisions and state-level laws have undermined this principle. “Freedom of religion is the private decision of a person. The state has no business to interfere in the private choices of people,” Prof. Mustafa stressed.

Prof. Mustafa raised concerns about so-called “Freedom of Religion” or “love jihad” laws enacted in several Indian states, which in practice restrict religious conversions and impose severe penalties. He warned that new amendments in the states of Rajasthan and Uttarakhand, requiring prior approval from district officials and public disclosure of personal details before conversion, endanger both individuals and religious leaders, potentially exposing them to violence.

Dr Faustina Pereira, a practicing lawyer in the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, highlighted a dramatic deterioration in the human rights situation in Bangladesh, marked by repression of religious and ethnic minorities and a shrinking space for free expression.

Dr Pereira stressed that while Bangladesh’s Constitution enshrines secularism (Article 12) alongside Islam as the state religion (Article 2A), the judiciary often avoids addressing the rights of minorities explicitly. She noted that the Constitution guarantees equal rights for Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, and other religious communities, yet in practice, these protections remain precarious.

According to Dr Pereira, Bangladesh stands at constitutional crossroads, with proposals to remove secularism, a founding principle, from the Constitution’s preamble. She warned that such reforms could erode democratic ideals and exacerbate persecution of minorities. “Secularism is a core tenet of Bangladesh’s founding vision. Eliminating it risks altering the nation’s very identity,” she said.

Vijula Arulanantham, Attorney-at-Law from Sri Lanka, drew attention to how Sri Lanka’s constitutional framework disadvantages minority religious and ethnic communities.

Ms Arulanantham highlighted the Sri Lankan Constitution’s Article 9, which gives Buddhism the “foremost place,” often leaving minorities disadvantaged. She noted that laws intended to protect rights are sometimes misused against minorities, and that courts have been reluctant to extend protections beyond some democratic values.

She also highlighted that while the Constitution pledges equal rights, in practice minority communities often face discrimination, and the constitutional framework does not always safeguard pluralism.

Advocate Tahir Bashir, a practicing lawyer in Lahore High Court in Pakistan and Legal Advisor at the Centre for Legal Aid Assistance and Settlement (CLAAS) shared that while Pakistan’s Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, equality, and minority rights, the country’s judiciary continues to face severe challenges in upholding the constitutional guarantees due to external factors. He identified the judiciary’s inconsistent rulings, public pressure, and societal prejudices as major obstacles.

“Judges often face mob backlash, particularly in blasphemy cases, which results in disproportionate punishment and long incarcerations for minorities,” Adv. Bashir said.

A committed human rights lawyer, who regularly defends individuals accused of blasphemy, he noted that despite progressive judgments in some cases, the effective implementation of legal remedies remains weak due to institutional inertia and fear among legal professionals.

Adv. Bashir also drew attention to persistent issues of false blasphemy accusations, mob violence, targeted killings, and attacks on places of worship. “To effectively protect minority rights, Pakistan needs clearer legislation, judicial consistency, and effective enforcement of laws,” he urged.

He further outlined the legal interventions of CLAAS in defending Christians facing persecution and wrongful imprisonment under blasphemy charges, emphasising the urgent need for systemic reforms to ensure equality and justice.

Dr Zainal Abidin Bagir, Director of the PhD Programme in Inter-religious Studies, Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies, Universitas Gadjah Mada, explained that in Indonesia, the revitalisation of blasphemy laws and local discriminatory regulations has deepened vulnerabilities for minorities.

Despite Indonesia’s constitutional guarantees, the judiciary often struggles to protect religious freedom due to political influence and public pressures, stated Dr Bagir. He stressed that litigation alone cannot advance freedom of religion and belief in Indonesia. While the Constitutional Court has played an important role in interpreting the law through human rights principles, he emphasised that judicial review must be supported by broader strategies: “Legal advocacy needs a campaign approach: building support from communities, religious groups, academics, and even government actors.”

Dr Bagir added that law and politics are inseparable, and effective protection of religious freedom requires advocacy that takes account of the political context.

Across these contexts, a common theme emerged: while constitutions across Asia guarantee religious freedom, courts often operate under political constraints and societal pressure, undermining protections for minorities.